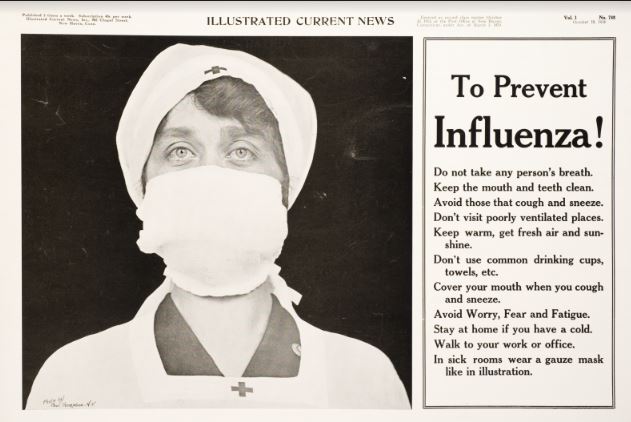

Home-Made Masks: Useful but Not Enough in 1918;

Useful but Not Enough Now

Marian Moser Jones

University of Maryland School of Public Health

[email protected]

Courtesy Beth Hundt, PhD, RN

How many masks can you make? Friends with sewing machines – many drowning in child care, elder care, and work – have been inundated with these demands through social media.

Posting homemade mask patterns and tutorials online, an improvised army of volunteers is producing thousands of non-regulation face coverings for COVID-19 first responders, and is asking you to do so too.

Yes, it is noble that citizens have taken matters into their own hands, as the supply chain for N95 masks and other Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) remains entangled in politics, red tape, and profiteering, forcing health care workers on the pandemic’s frontlines to wear bandanas and sports goggles to protect themselves.

But while this grassroots response may seem like a heart-rending return to the homespun American voluntarism of yesteryear, history tells us a more complicated story.

As a public health historian who’s studied the American Red Cross, I am reminded of the eight million female Red Cross volunteers who organized industrial-style assembly lines to roll bandages and sew garments for wounded troops during World War I. When pandemic influenza arrived in 1918, they switched gears to churn out 1.4 million gauze masks.

In Boston, the first U.S. city struck by pandemic flu, 537 volunteers from the local chapter worked for 17 days straight to produce 83,606 masks, according to chapter records. The Red Cross Motor Corps, affluent women who drove their own cars on Red Cross errands, delivered the masks to hospitals, local organizations, and private homes.

Other cities followed suit, with 30,000 chapter sewing rooms participating. Red Cross publications touted the efficiency of this system. “One day an S.O.S. call came into central headquarters,” Red Cross leader Henry Davison later wrote. “Contagion was rampant at an Iowa camp and the hospital must have ward masks. [The] Chicago [office] had none on hand, but she knew where they were to be had, and in three days twenty thousand of the precious filters were on their way from a northern neighbor.”

However, news reports depict a less organized picture. In Richmond, Virginia, the local chapter announced it would sell home-made masks for two cents apiece. When customers lined up at chapter headquarters, (likely spreading flu), the chapter soon ran out. Moreover, given that most white hospitals refused to treat African Americans even during the pandemic, and that many Black women reported being rebuffed when trying to volunteer at local chapters, it is also highly likely that chapters preferentially distributed home-made masks to white hospitals and white people.

Additionally, mask makers likely exposed themselves to flu: photographs of these activities depict 30 or more uniformed volunteers working shoulder-to-shoulder in crowded rooms. Such gatherings ran counter to local public health officials’ bans on public gatherings to stem the spread of flu. Considering that many U.S. women engaged in such unpaid work due to social pressure to demonstrate their patriotism, and that “slackers” who failed to do so were publicly shamed, the additional disease exposure that mask-making women incurred becomes more ethically problematic.

National Library of Medicine

Overall, these collective mask-making projects exemplify the patchwork nature of the social restrictions that local officials in the U.S. tried to impose to stem the flu in 1918 and 1919. The delayed, volunteer-driven response in many U.S. cities, along with the staggering mortality from influenza, serves as an object lesson about the weaknesses of federalism in addressing a pandemic.

In World War II, millions of American women again gathered in Red Cross sewing rooms to roll bandages and make surgical supplies. But by then, the War Department deemed that homemade medical supplies failed to meet modern hospital standards. Instead it promised to use these items to meet shortages in military hospitals within the U.S., while contracting with commercial firms to obtain bandages “especially processed, sterilized and sealed for shipment to the front lines.”

We can learn from this development. Just as hand-rolled bandages had become backup supplies by the Second World War, home-made masks in 2020 should be reserved for people in the second line of vulnerability – workers who cannot avoid contact with the public but are not pandemic health care workers or first responders.

Meanwhile, we should continue to collectively insist that government and manufacturing sectors be mobilized immediately to produce and distribute sufficient, adequate, top-quality PPE for the workers on the front lines of this pandemic, the way the War Department insisted on providing professional-grade hospital supplies for troops fighting in World War II. While homespun solutions may help, they are insufficient to address this 21st-century crisis.

|